Qakbot Actors Distribute Ransom Knight Ransomware, Storm-0324 Leverages Microsoft Teams to Distribute JSSLoader, a new APT Grayling Emerges, and Rhysida Ransomware Operators Leverage Valid VPN Credentials

This week: threat actors deliver Ransom Knight ransomware via phishing emails, a critical vulnerability in NetScaler Gateway is exploited, APT Storm-0324 used Microsoft Teams to spread the JSSLoader malware, and a new APT Grayling emerges–all of this plus the latest from data leak sites and 8 new CVEs.

In our latest Cyber Intelligence Brief, Deepwatch ATI looks at new threats and techniques to deliver actionable intelligence for SecOps organizations.

As a leading managed security platform, Deepwatch stands at the forefront of delivering actionable intelligence to keep pace with the ever-evolving threat landscape. Through the Deepwatch Adversary Tactics and Intelligence (ATI) team, we arm your organization with essential knowledge, giving you the power to proactively spot and neutralize risks, amplify your security protocols, and shield your financial stability.

Each week we look at in-house and industry threat intelligence and provide ATI analysis and perspective to shine a light on a spectrum of cyber threats.

This Week’s Source Material

- CISCO Talos: Qakbot-affiliated actors distribute Ransom Knight malware despite infrastructure takedown

- IBM X-Force: X-Force uncovers global NetScaler Gateway credential harvesting campaign

- Trellix: Storm-0324 to Sangria Tempest Leads to Ransomware Capabilities

- Symantec: Grayling: Previously Unseen Threat Actor Targets Multiple Organizations in Taiwan

- Trellix: Rhysida Ransomware

- The Latest Additions from Data Leak Sites

- CISA Adds 8 CVEs to its Known Exploited Vulnerabilities Catalog

Qakbot Actors Distributing Ransom Knight Ransomware and Remcos backdoor via ZIP Files

Qakbot – Ransom Knight Ransomware – Remcos Backdoor – ZIP, LNK, and XLL Files – Industries/All

Overview & Background

Research from Cisco Talos titled “Qakbot-affiliated actors distribute Ransom Knight malware despite infrastructure takedown” details the activities of threat actors behind the Qakbot malware who have been distributing Ransom Knight ransomware and the Remcos backdoor via phishing emails since early August 2023. The blog post aims to shed light on the persistence of these threat actors, especially in the wake of law enforcement actions against their infrastructure. The blog post analyzes the metadata in LNK files used in this campaign and draws connections to previous Qakbot campaigns, providing insights into the threat actors’ evolving tactics and techniques.

Historically, Qakbot has been a significant malware strain that has evolved over the years to include various capabilities. In late August 2023, the FBI, in collaboration with international partners, took effective action against Qakbot by seizing its infrastructure and cryptocurrency assets. This move was seen as a considerable blow to the group’s operations. Despite this takedown, Qakbot-affiliated actors have shown resilience by distributing the Ransom Knight ransomware and Remcos backdoor. Ransom Knight is an updated version of the Cyclops ransomware-as-a-service, which its developers announced in May 2023. Remcos is a known backdoor that provides threat actors with remote access capabilities, further enhancing their ability to compromise and control infected systems.

Threat Analysis

This campaign was initiated in early August 2023, notably before the FBI seized Qakbot infrastructure, and has been ongoing. However, we do not know if the takedown action only impacted the command and control (C2) servers. If the takedown action only affected the C2 servers, this would leave the spam delivery infrastructure operational.

Talos attributes this campaign to Qakbot affiliates based on the metadata found in LNK files. These files were created on the same machine used in previous Qakbot campaigns, specifically the “AA” and ”BB” campaigns. Although Talos has not observed the distribution of Qakbot post-takedown, the developers behind Qakbot were not apprehended, and, therefore,can rebuild the Qakbot infrastructure.

The distribution involves LNK files contained within ZIP files with financial themes. These LNK files download the Ransom Knight payload. While we can not determine the exact delivery method, Qakbot has traditionally been distributed via phishing emails; for this reason, these are likely distributed via email. The intended targets include Italian and English speakers, as the filenames are in English and Italian. Along with the LNK files, the Zip files also contain an XLL file, an extension for Excel add-ins. Cisco’s analysis shows that these XLL files are the Remcos backdoor, providing threat actors access post-infection.

The Qakbot-affiliated actors’ operations are likely for financial gain, supported by their deployment of ransomware. Their objectives are to target systems for unauthorized access and disrupt operations by deploying ransomware and a backdoor. Regarding capabilities, the threat actors have the knowledge and skills to evolve their tactics and techniques in response to external pressures, like the recent law enforcement actions.

Risk & Impact Assessment

The most pressing risks are the loss of confidentiality and availability, primarily due to the Remcos backdoor and Ransom Knight ransomware. Threat actors can obtain unauthorized access, disclose sensitive information, and disrupt operations. However, there is a risk stemming from the loss of integrity. It is unlikely, but the impact of data destruction caused by flawed ransomware encryption or victims not receiving the decryption key is significant. The FBI has also observed the deployment of data wipers in some ransomware attacks. While there is no evidence that the threat actors will deploy a data wiper, there is a remote chance that the threat actors will deploy one to force victims to pay the ransom.

Threat Actors Exploit CVE-2023-3519 to Modify Login Page, Harvest Credentials

NetScaler Gateway CVE-2023-3519 – Vulnerability Exploitation – Credential Harvesting – Industries/All

Overview & Background

A blog post from IBM X-Force titled “X-Force uncovers global NetScaler Gateway credential harvesting campaign” details a campaign where threat actors exploited the vulnerability identified as CVE-2023-3519 to insert a PHP webshell to ultimately capture user credentials. The blog post aims to shed light on this specific campaign, emphasizing the increased interest from cyber criminals in credentials. The blog post examines the TTPs (Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures) used by the threat actors, the affected systems, and the potentially compromised data.

CVE-2023-3519 is a critical-severity vulnerability found in NetScaler ADC (formerly Citrix ADC) and NetScaler Gateway (formerly Citrix Gateway). This vulnerability allows for unauthenticated remote code execution. It can be exploited if an appliance is configured as a gateway (VPN virtual server, ICA Proxy, CVPN, RDP Proxy) or an authentication virtual server (AAA virtual server). The vulnerability has a Proof of Concept (PoC) exploit and a Metasploit module.

Threat Analysis

In September 2023, IBM X-Force observed threat actors exploiting CVE-2023-3519 to insert a malicious script into the HTML content of the authentication web page. This script, once embedded, was designed to capture user credentials. The threat actors appended this script to the legitimate “index.html” file. This malicious addition would then load a remote JavaScript file that attaches a function to the “Log On” element in the VPN authentication page. This function collects the username and password information during the authentication process and transmits it to a remote server.

The threat actors initiated the exploit chain by sending a web request to “/gwtest/formssso? event=start&target=”, which triggered the memory corruption documented in CVE-2023-3519. This web request allowed them to write a simple PHP web shell to /netscaler/ns_gui/vpn. Once they had interactive access through this PHP web shell, the actors retrieved the contents of the “ns.conf” file on the device. They then appended custom HTML code to “index.html,” which references a remote JavaScript file hosted on actor-controlled infrastructure.

The JavaScript code inserted in “index.html” retrieves and executes additional JavaScript code to attach a custom function to the “Log_On” element, collecting the form data containing the username and password information. Upon authentication, this data is sent to a remote host via an HTTP POST request.

The threat actors’ intention behind the campaign is highly likely for financial gain, as evidenced by their harvesting user credentials from almost 600 targets, primarily in the United States and Europe. However, there is a remote possibility that the intention is to facilitate intelligence collection. Their objectives were clear: exploit NetScaler Gateways’s vulnerability, modify NetScaler Gateway login pages, and capture and exfiltrate user credentials.

In terms of capabilities, the actors showcased competence in web-based attack techniques, from exploiting a known vulnerability to deploying malicious scripts and setting up infrastructure to capture and transmit the harvested data. Their use of JavaScript for credential harvesting and deploying a PHP web shell further underscores their operational proficiency in this campaign.

Risk & Impact Assessment

The exploitation of CVE-2023-3519 poses a pronounced risk to organizations, primarily through the loss of confidentiality from harvesting user credentials, which threatens organizational mission, functions, and assets. An elevated risk to availability emerges with the potential acquisition of these credentials by ransomware actors, leading to possible operational disruptions. While there’s a remote risk to integrity, the direct impact on organizations is substantial. Unauthorized access can precipitate significant cyber incidents, like data theft and ransomware, leading to setbacks affecting net sales, revenues, and ongoing operations. The exfiltration of sensitive data jeopardizes proprietary information and organizational reputation; if instigated by ransomware actors, operational disruptions can halt business processes, eroding stakeholder trust. Though a remote probability, the potential destruction or loss of data would demand extensive recovery efforts and incur considerable costs.

Storm-0324 Leverages Microsoft Teams to Distribute JSSLoader, Deploys Ransomware

Storm-0324 – Microsoft Publisher CVE-2023-2175 – Microsoft Teams – Phishing – JSSLoader – Ransomware – Industries/All

Overview & Background

A blog post from Trellix titled “Storm-0324 to Sangria Tempest Leads to Ransomware Capabilities” details the activities of the threat actor group known as “Storm-0324.” This group has been observed distributing the JSSLoader malware via Microsoft Teams phishing messages and passing access to Sangria Tempest (FIN7, Carbon Spider), affiliates of various ransomware operations, including CL0P. The blog post aims to shed light on the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) employed by Storm-0324, their collaboration with other threat actor groups, and the subsequent risks posed by their activities. The blog post analyzes the malware distribution methods, infection vectors, and the various payloads associated with Storm-0324’s operations.

Storm-0324 is a financially motivated threat actor group that has historically been associated with distributing phishing emails to gain initial access to compromised systems. Their modus operandi often involves gaining an initial foothold in a system and handing off access to other well-known ransomware groups. In the past, Storm-0324 has been linked to the distribution of various malware strains, including the Gozi InfoStealer, Nymaim downloader, and locker. Over time, Storm-0324 has employed various file types for its campaigns, including WSF, MS Office Doc, and VBS. Before their shift to JSSLoader, their arsenal included a range of payloads such as Gozi, Trickbot, Gootkit, Dridex, Sage, Gandcrab Ransomware, and IcedID.

Threat Analysis

Storm-0324 has demonstrated a consistent pattern of distributing malware through phishing campaigns. Their recent tactics involve leveraging Microsoft Teams as a platform for their phishing messages. Once they successfully gain initial access to a system, they often transition control, handing off the compromised system’s access to other ransomware groups. This behavior underscores their collaborative approach within the cyber threat landscape.

The malware of choice for Storm-0324 in their recent campaigns is the JSSLoader. Their methods of distribution have seen an evolution. Historically, they have utilized phishing emails with invoice themes, such as those mimicking DocuSign and Quickbooks, but are now using Microsoft Teams messages. These messages include documents or links that, when clicked, redirect targets to a SharePoint site hoisting a ZIP archive. This archive contained a compressed Windows Script File (WSF) that exploits CVE-2023-21715, a Microsoft security features bypass vulnerability. When clicking this file, it contacts a site that downloads an encoded VB script. This VB script contains another VB script that contacts another site that downloads the final payload, JSSLoader.

Upon successful device infection, JSSLoader initiates a series of activities, including generating a unique identifier for each infected device, gathering host information, creating an LNK file, and remote code execution. The unique ID allows the threat actor to track and manage individual infections. JSSLoader collects and transmits certain data types, such as logical drivers, hostname, username, domain name, system info (desktop file list, running process, installed application, PCinfo), and IP info. This collected data is then relayed to command and control servers operated by the threat actors. JSSLoader creates a shortcut Shell LNK in the startup folder to maintain persistence. A particularly concerning capability of JSSLoader is its ability for remote code execution. This capability allows the threat actor to not only utilize the initial functionalities of the malware but also to:

- Execute a randomly named file.

- Write a randomly named EXE file and execute it as a thread.

- Write blob content in a randomly named file and run it through PowerShell.

- Execute a PowerShell command.

- Write a randomly named DLL file and run it using rundll32.exe.

- Exfiltrate info from the victim’s machine.

The collaboration between Storm-0324 and other threat actor groups, especially Sangria Tempest (also known as FIN7, Carbon Spider) and TA543, is evident. However, Microsoft states that Storm-0324 overlaps with TA543. These groups often capitalize on the initial access provided by Storm-0324 to launch their ransomware attacks. Past associations between Sangria Tempest and Storm-0324 have seen the distribution of malware strains like the Gozi InfoStealer and Nymaim downloader and locker. The current trend, however, sees Storm-0324 distributing the JSSLoader before initiating collaborations with other ransomware entities.

Storm-0324 operates with clear financial motivations, consistently leveraging phishing campaigns, recently through modern platforms like Microsoft Teams, to gain unauthorized access to systems. Their objectives encompass a range of malicious activities, from unauthorized system access and extracting specific system and user data to monetizing this unauthorized access by collaborating with ransomware actors or selling it outright. Their capabilities are multifaceted: while they demonstrate expertise in phishing and deploying malware, they rely on tools like JSSLoader for data harvesting, persistence, and remote code execution. However, there is a remote probability that JSSLoader is not exclusive to Storm-0324, and other threat actors could have access to the malware. Their collaborations with other threat groups amplify their reach and potential impact in the cyber threat landscape.

Risk & Impact Assessment

If devices within an organization are successfully infected by JSSLoader, as deployed by Storm-0324, the potential repercussions are diverse. Operational disruptions could lead to significant downtimes, directly impacting sales, revenues, and ongoing business operations. The exfiltration of sensitive data threatens the confidentiality of proprietary and customer information and could result in regulatory fines, legal actions, and the associated costs of breach notifications and compensations. Furthermore, the organization could suffer from reputational damage, losing trust among customers and partners, potentially affecting future business opportunities and contracts. The combined direct and indirect costs and potential revenue losses underscore the material impact on the organization’s financial health and sustainability.

Unknown APT Targeted Organizations in Taiwan, the Pacific Islands, Vietnam, and the U.S., Using Various Tools and Unique Techniques

Grayling – CVE-2019-0803 – DLL Sideloading – Cobalt Strike – Havoc – NetSpy – Mimikatz – Manufacturing – Information – Professional, Technical, and Scientific Services

Overview & Background

A blog post from Symantec titled “Grayling: Previously Unseen Threat Actor Targets Multiple Organizations in Taiwan” details the activities of a previously unidentified APT group named Grayling. This group has been observed targeting multiple organizations in Taiwan’s manufacturing, IT, and biomedical sectors using custom malware and several public tools. The blog post aims to shed light on this previously unknown threat actor and their tactics, techniques, and procedures. The analysis within the blog post is based on the observed activities of Grayling from February 2023 to at least May 2023, focusing on their distinctive use of a DLL sideloading technique and their primary motivation of intelligence gathering.

Threat Analysis

Grayling’s operations between February 2023 and at least May 2023 impacted organizations in Taiwan’s manufacturing, IT, and biomedical sectors, a government agency in the Pacific Islands, and organizations in Vietnam and the US. A hallmark of Grayling’s modus operandi is their distinctive DLL sideloading technique, which employs a custom decryptor to deploy payloads effectively. This technique sets them apart from many other threat actors in the cyber landscape.

Symantec observed web shell deployment on some victim computers before deploying additional payloads, providing evidence supporting Grayling’s exploiting public-facing infrastructure for initial access into victim systems. However, this has yet to be verified. Their signature DLL sideloading method proved pivotal for Grayling, enabling them to load a variety of malicious payloads, with Cobalt Strike, NetSpy, and the Havoc framework being the most prominent.

Once inside, Grayling is methodical and deliberate. They escalate their privileges, scan the network to understand the environment better, and deploy additional malicious payloads using downloaders. Their toolkit is diverse: the Havoc framework, introduced in early 2023, is a versatile open-source post-exploitation command-and-control system. It’s capable of a wide range of activities, from managing processes to running shellcode, and its cross-platform nature makes it particularly potent. While having legitimate penetration-testing uses, Cobalt Strike is a favored tool among threat actors for its multifunctional capabilities. Grayling also employed NetSpy, a publicly available spyware tool, and exploited the CVE-2019-0803 vulnerability in Windows for privilege escalation. Their operations within the compromised network are extensive, including querying the Active Directory for network mapping and using the Mimikatz tool for credential dumping.

The typical progression of a Grayling attack involves DLL sideloading through the exported API SbieDll_Hook, leading to deploying an array of tools. Notably, Symantec observed the deployment of an unknown payload sourced from imfsb.ini. They also engaged in various post-exploitation activities, including terminating processes as listed in a specific file named processlist.txt and subsequently downloading the Mimikatz tool.

Grayling exhibits a broad range of objectives and capabilities, targeting sectors such as manufacturing, IT, biomedical, and government agencies across diverse geographies like Taiwan, the Pacific Islands, Vietnam, and the U.S. Their objectives, while encompassing unauthorized system access, remain somewhat enigmatic due to the absence of concrete evidence pointing towards data exfiltration or intelligence-relevant data access. Their technical prowess is evident in their use of custom tools, exploitation of known vulnerabilities, and stealthy operational patterns. Despite the ambiguity surrounding their primary intentions, their objectives and capabilities suggest a potential for diverse motivations, from disruption to financial gain. The combination of their objectives and capabilities underscores their multifaceted threat to the targeted sectors.

Risk & Impact Assessment

Grayling’s systematic approach to system access, amplified by their use of tools like Cobalt Strike and NetSpy, presents a pronounced risk to the confidentiality of sensitive data, especially within targeted sectors such as manufacturing, IT, biomedical, and government agencies. Unauthorized access could lead to significant operational disruptions, financial implications from the potential unauthorized disclosure of intellectual property or trade secrets, and reputational damage due to diminished trust and possible legal repercussions. While the evidence suggests a remote risk to data or system integrity and potential disruptions to availability, the primary concern remains the threat to confidentiality, given Grayling’s capabilities and targeting pattern.

Rhysida Ransomware Operators Leveraged Valid VPN Credentials to Infiltrate a Network, Exfiltrate Data, and Encrypt Linux Systems

Rhysida Ransomware – Valid Credentials – Data Exfiltration – SystemBC – PowerGrab – Industries/All

Overview & Background

Research from Trellix titled “Rhysida Ransomware” details the activities and techniques of the Rhysida ransomware family, focusing on an anonymized version of an attack by the Rhysida ransomware operators. The blog post aims to raise awareness among defenders by detailing the operator’s techniques, sharing factual observations, and offering insights to improve security postures. The blog post analyzes the technical aspects of the ransomware and the operator’s modus operandi and provides a deep dive into the ransomware’s capabilities and internals.

Rhysida ransomware first emerged in the cyber threat landscape when it was posted about in May by the MalwareHunterTeam. It gained significant attention and was subsequently documented by CheckPoint and TrendMicro in August 2023. These reports highlighted the potential overlap or even rebranding of Rhysida with the Vice Society ransomware gang. Vice Society, known for using the Buran/Zeppelin ransomware in the past, has shown a pattern of not tying itself exclusively to a single ransomware “brand,” leading to speculations that Vice Society might be using multiple ransomware strains, with Rhysida being one of them or possibly adopting Rhysida as their primary ransomware tool.

Threat Analysis

The Rhysida ransomware operators gain initial access by using valid VPN credentials. Once inside, they manually collect valuable data, compress it, exfiltrate it, and then deploy the ransomware. This infiltration method was made possible due to the absence of multi-factor authentication (MFA), allowing the threat actor to access the corporate environment with a username and password. It is unknown how the operators obtained the credentials, but one possibility includes purchasing them on cybercriminal marketplaces. The victim may have been infected with an infostealer, and the threat actors offered the data (also known as logs) from this stealer to a marketplace where the ransomware operators purchased them.

Following the initial access, the threat actors swiftly move to the escalation and lateral movement phase. They conduct network reconnaissance and user enumeration, targeting services such as DNS, HTTP(S), SSH, FTP, SMB, RDP, and Kerberos. Based on their findings, they laterally move through the network using SMB and RDP. They take over additional accounts through password spraying and exploit privilege escalation vulnerabilities to establish their presence further. In this attack, the operators deployed the SystemBC backdoor, a PowerShell-based backdoor complemented by the PowerGrab tool. These tools extracted information and credentials from the endpoints they were deployed on. They also removed terminal histories and related files and directories to cover their tracks.

At this point, the operators moved on to data collection and exfiltration, where the threat actors identify and exfiltrate data they deem valuable. The degradation of recovery and system security services is the next step. The threat actor manually removes logical disks from the backups, and then the infrastructure is encrypted using an ESXi ransomware sample. A Group Policy Object (GPO) is set to display the ransom note upon logging in. With the assistance of PsExec, the initialization script is executed, the ransomware is copied to the target system using valid user credentials, and the ransomware is executed.

The technical analysis of the ransomware reveals that upon execution, it uses the current time to seed its random generator and determines the number of CPUs using GetSystemInfo. It then captures command-line arguments with getcwd. The ransomware logs its activities to the standard output for the operator’s visibility. It uses a buffer to retain the handles of the newly created threads, with the number of threads equating to the number of CPUs. The ransomware’s command-line interface options and handling are intricate, with encryption being a primary focus. Rhysida employs ChaCha20 for file encryption. The key and IV used are encrypted with the RSA public key imported at the ransomware’s start, meaning the corresponding RSA private key is required for decryption.

The threat actors behind the Rhysida ransomware primarily intend to disrupt operations for financial gain, leveraging their capabilities to infiltrate networks, exfiltrate sensitive data, and deploy ransomware. Their main objective is to extort victims into paying a ransom by threatening the integrity and availability of data and systems and leaking sensitive information. While the exfiltration of data primarily reinforces the extortion threat, there’s a remote possibility that, if nation-state sponsored, the data could facilitate intelligence collection, with ransom proceeds potentially funding future operations. Their diverse capabilities, from technical proficiency in various services to data handling and ransomware deployment, underscore their multifaceted threat profile.

Risk & Impact Assessment

A Rhysida ransomware attack poses significant risks to an organization’s confidentiality and, most prominently, availability, with a lesser risk to integrity. Threat actors accessed systems and exfiltrated data, threatening confidentiality. The encryption of data, combined with backup removal, jeopardizes data availability and suggests potential data destruction. The impacts are multifaceted: immediate operational disruptions could halt business functions. Direct and indirect financial costs could arise from ransom payments, IT recovery, lost revenues, and eroded customer trust. Reputational damage could deter customer retention and acquisition. Potential regulatory fines and legal actions might emerge, especially if personal data is compromised. Finally, organizations would likely face increased future security costs and resource-intensive and financial impacts from negotiations and communications with threat actors and stakeholders.

Latest Additions to Data Leak Sites

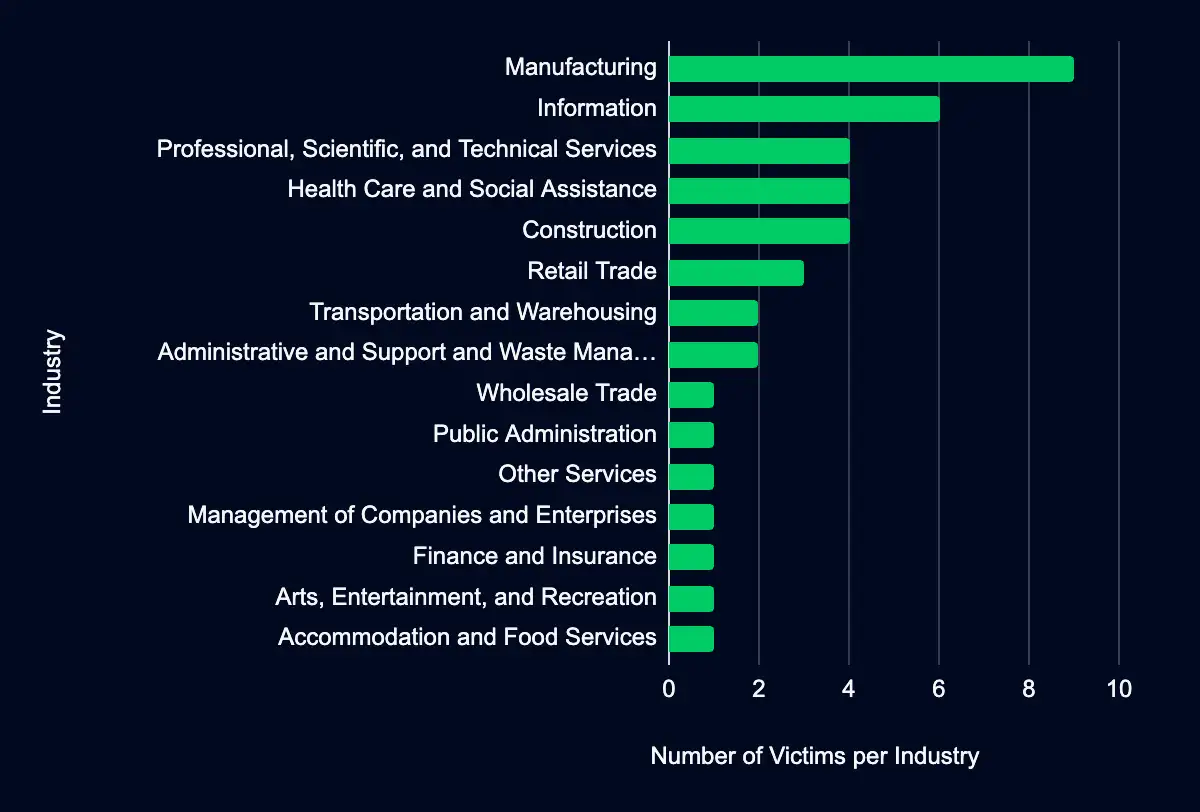

Manufacturing – Information – Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services – Health Care and Social Assistance – Construction

In the past week, monitored data extortion and ransomware threat groups added 41 victims to their leak sites. Of those listed, 21 are based in the USA. Manufacturing was the most affected industry, with nine victims. This industry is followed by 6 in Information and four in Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services, Health Care and Social Assistance, and Construction. This information represents victims whom cybercriminals may have successfully compromised but opted not to negotiate or pay a ransom. However, we cannot confirm the validity of the cybercriminals’ claims.

CISA Adds 8 CVEs to its Known Exploited Vulnerabilities Catalog

Adobe CVE-2023-21608 – Cisco CVE-2023-20109 – Microsoft CVE-2023-41763 – Microsoft CVE-2023-36563 – IETF CVE-2023-44487 – Atlassian CVE-2023-22515 – Progress CVE-2023-40044 – Apple CVE-2023-42824

Within the past week, CISA added eight CVEs to the catalog, affecting Adobe, Cisco, Microsoft, IETF, Atlassian, Progress, and Apple products. Threat actors can exploit these vulnerabilities for code execution in the user context, execution of malicious code or device crashes, privilege escalation, information disclosure, distributed denial-of-service attacks, unauthorized account creation and access, and remote command execution on the underlying operating system. It is crucial to promptly apply updates or follow vendor instructions to mitigate these vulnerabilities, with CISA recommending mitigative action occur between 13 and 31 October 2023.

| CVE ID | Vendor | Product | Description | CISA Due Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVE-2023-21608 | Adobe | Acrobat and Reader | Adobe Acrobat and Reader contains a use-after-free vulnerability that allows for code execution in the context of the current user. | 2023-10-31 |

| CVE-2023-20109 | Cisco | IOS and IOS XE | Cisco IOS and IOS XE contain an out-of-bounds write vulnerability in the Group Encrypted Transport VPN (GET VPN) feature that could allow an authenticated, remote attacker who has administrative control of either a group member or a key server to execute malicious code or cause a device to crash. | 2023-10-31 |

| CVE-2023-41763 | Microsoft | Skype for Business | Microsoft Skype for Business contains an unspecified vulnerability that allows for privilege escalation. | 2023-10-31 |

| CVE-2023-36563 | Microsoft | WordPad | Microsoft WordPad contains an unspecified vulnerability that allows for information disclosure. | 2023-10-31 |

| CVE-2023-44487 | IETF | HTTP/2 | HTTP/2 contains a rapid reset vulnerability that allows for a distributed denial-of-service attack (DDoS). | 2023-10-31 |

| CVE-2023-22515 | Atlassian | Confluence Data Center and Server | Atlassian Confluence Data Center and Server contains a broken access control vulnerability that allows an attacker to create unauthorized Confluence administrator accounts and access Confluence. | 2023-10-13 |

| CVE-2023-40044 | Progress | WS_FTP Server | Progress WS_FTP Server contains a deserialization of untrusted data vulnerability in the Ad Hoc Transfer module that allows an authenticated attacker to execute remote commands on the underlying operating system. | 2023-10-26 |

| CVE-2023-42824 | Apple | iOS and iPadOS | Apple iOS and iPadOS contain an unspecified vulnerability that allows for local privilege escalation. | 2023-10-26 |

Let’s Secure Your Organization’s Future Together

At Deepwatch, we are committed to helping organizations like yours navigate the intricate world of cyber threats. Our cybersecurity solutions are designed to stay ahead of the curve, providing you with the proactive defenses needed to protect your organization from these threats.

Our team of cybersecurity professionals is ready to evaluate your systems, provide actionable insights, and implement robust security measures tailored to your needs.

Don’t wait for a cyber threat to disrupt your operations. Contact us today and take the first step towards a more secure future for your organization. Together, we can outsmart the threats and secure your networks.

What We Mean When We Say

Estimates of Likelihood

We use probabilistic language to reflect the Intel Team’s estimates of the likelihood of developments or events because analytical judgments are not certain. Terms like “probably,” “likely,” “very likely,” and “almost certainly” denote a higher than even chance. The terms “unlikely” and “remote” imply that an event has a lower than even chance of occurring; they do not imply that it will not. Terms like “might” reflect situations where we are unable to assess the likelihood, usually due to a lack of relevant information, which is sketchy or fragmented. Terms like “we can’t dismiss,” “we can’t rule out,” and “we can’t discount” refer to an unlikely, improbable, or distant event with significant consequences.

Confidence in Assessments

Our assessments and projections are based on data that varies in scope, quality, and source. As a result, we assign our assessments high, moderate, or low levels of confidence, as follows:

High confidence indicates that our decisions are based on reliable information and/or that the nature of the problem allows us to make a sound decision. However, a “high confidence” judgment is not a fact or a guarantee, and it still carries the risk of being incorrect.

Moderate confidence denotes that the information is credible and plausible, but not of high enough quality or sufficiently corroborated to warrant a higher level of assurance.

Low confidence indicates that the information’s credibility and/or plausibility are in doubt, that the information is too fragmented or poorly corroborated to make solid analytic inferences, or that we have serious concerns or problems with the sources.

Share